Fashion world goes through ebbs and flows of change each season... change of trends, change of aesthetics. Some changes remain, some changes evolve into something else. But to find a constant in the conception of Western fashion is truly hard to do, and even harder to agree on. South Asian fashion does not suffer from that sort of rudderless indulgence. For better or for worse, for summer or for winter, for fast fashion or for Haute' couture, countries within the subcontinent circles back to one singular garment in many designs, many forms, many many many iterations...it is the Saree.

So it is no surprise that a south Asian editorial at an anglo-french avant-garde magazine would be a celebration of that specific garment, a love note to that whimsical, functional, romantic, moving one-piece garment that is loved by millions of women and provides one of the most distinct yet easily accessible fashion statement of all of fashion history.

The saree industry in Bangladesh and India brings in global numbers and can out-compete the likes of Balenciaga and Dior any day of the week and twice on Friday. But as it is with every single market structure, not all sarees are made equal. There are sarees made by power looms in minutes for the fast fashion market, and there are heritage sarees such as Jamdani made by artisans with months-long weaving for the bridal market. But as the middle class of South Asia expands, the market to have slow fashion (as in sustainable, organic) sarees are booming. And Bangladesh, being one of the key players in the saree market has now started addressing that gap between the artisans and the automation, that gap between a product that lasts and a product that barely lasts a few months. That market is opening up, that market is blowing up, that market is where the next generation of Couture-ists would come from.

On that juxtapose enter Aranya. With the focus of reviving the use of natural dye, Aranya came to existence in 1990 and through both commercial and aesthetic evolution has reached a point where its products are one of the very few that address social-economic responsibilities while pushing an aesthetic that is avant-garde yet deeply rooted in the legacy of the artisans working with heritage crafts from Bangladesh. Aranya in many ways is the only real game in town when it comes to sustainable fashion working on ethical fashion with a transparent supply chain that is able to take on increased environmental responsibilities and production goals. Aranya's creative director Nawshin Khair is responsible for bridging the tales of its artistic process and opening up Aranya to the outside world, after all she is the one who had the clarity of vision of bringing in a creative team that works globally as opposed to locally. So her long term strategy to make Aranya foundationally comfortable in both eastern and western realms is not a flash in the pan. She is gradually shaping up the brand to be the heir apparent in the fair trade ethnic fusion fashion market. So it is no surprise that Deux along with other Conde’ Nast Magazines (like Vogue Italia) would be interested in an editorial that encapsulates that legacy of whimsy and functionality while being deeply entrenched in the romanticism that sarees bring to millions of women (and men).

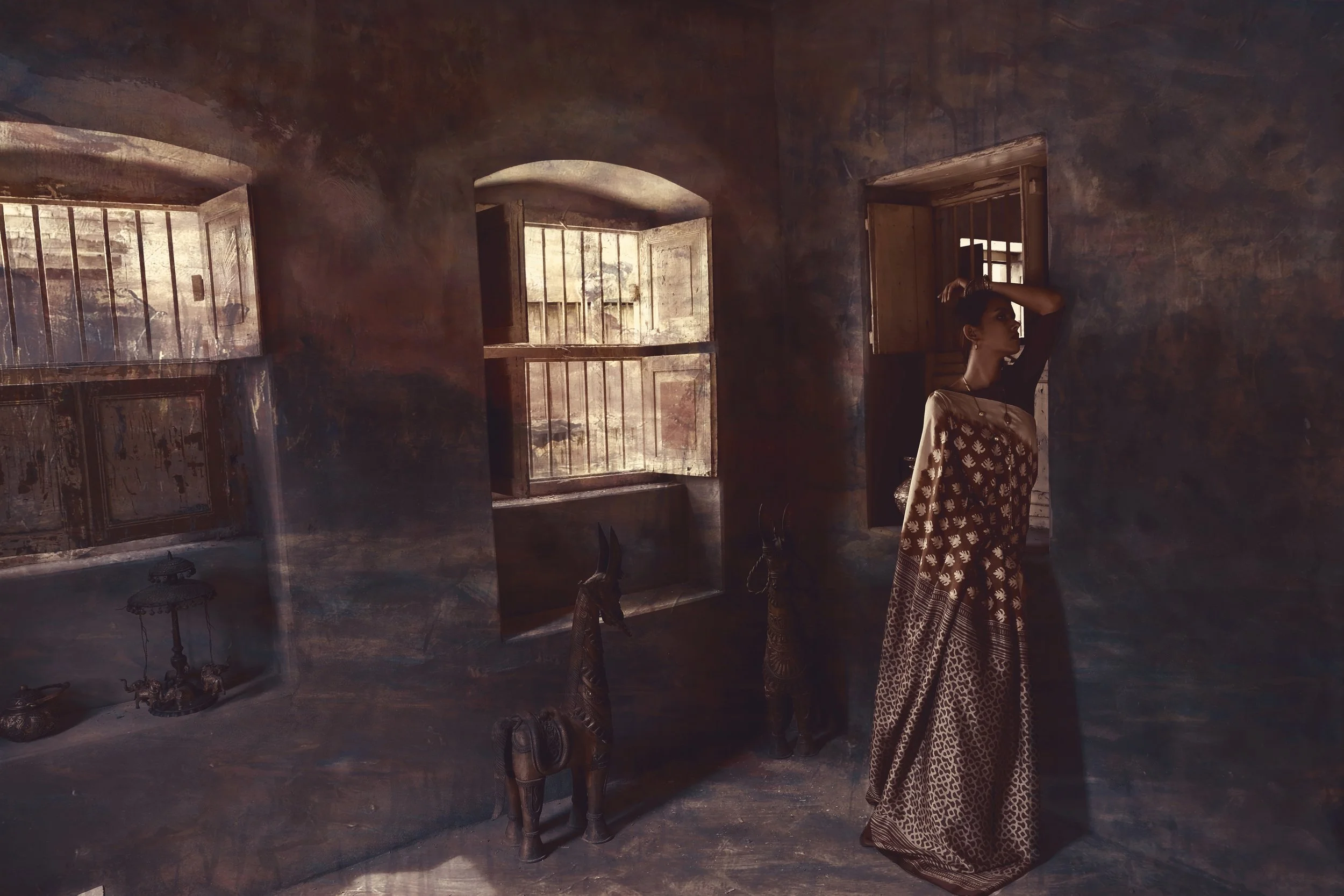

This editorial series, shot by Smithsonian artist and Vogue photographer, Omi is a testament to Aranya's ability to rise above boundaries of nationality and tribalism. It is a testament to art's power to introduce us to visuals that are so alien, so beautiful, so surreal yet so very close to our hearts. So it is no surprise that we are in love with these sets of photographs that quiets our senses, makes our eyes soft with unfettered romanticism. It is no surprise that this is fashion at its finest, deepest, and purest.

The visual narrative easing from untouched images to photographs soaked in brooding colors, is an exploration of singularity as a form of storytelling. Each photographs is an editorial, yet they are also part of a grander narrative, like a Proust novel. And just like a Proust novel, the elaborate and the concise, comes together to quiet our senses into a lull of romanticism. Art was meant to be like this.